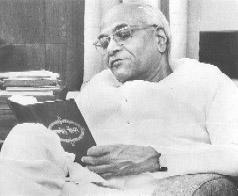

WAS GOENKA A BJP MAN?

Seems like. Hindustan Times editor Vir Sanghvi reviews a book on Ramnath Goenka by BG Vergehese. Here is the piece.

In the 1970s, when my involvement with journalism was largely restricted to seeing the press from the perspective of a reader, there was no doubt in my mind that Ramnath Goenka, the Indian Express’s feisty proprietor, was one of the good guys.

In those days, people like myself tended to judge journalists and their proprietors on a single criterion: where did they stand on the Indira Gandhi issue? For many of us, Mrs Gandhi was, indisputably, A Bad Thing. She had subverted democratic institutions, imposed an Emergency, censored the press, locked up the Opposition, foisted Sanjay — her thug-like son — on the country and sought to centralise all power within her office.

This consensus — even more popular within the liberal elite in those days than the secular consensus is today — governed our views on everyone and everything.

And, judged on this criterion, Goenka was a hero. He had seen through Mrs Gandhi as early as 1971 and had encouraged Frank Moraes, his editor, to oppose her even as Indira-mania swept India. He had offered support and shelter to Jayaprakash Narain (JP) during the movement for Total Revolution. And, during the Emergency, he had fought the might of the Establishment in the interests of press freedom.

By the 1980s, when I became a full-time journalist, I had begun to question my early judgement of Goenka. I first met him in 1981 when he offered me a job which I was unable to accept and, by 1984, knew him quite well on a personal level. I would often go to the Express penthouse at Bombay’s Nariman Point for lunch or dinner and he was kind enough to drop in at my home. On one memorable occasion, he even attended a large party for my wedding anniversary where he grinned wickedly as members of Bombay’s then nascent social scene (this was before the invention of Page Three) fawned over him.

In 1990, when my son was born, he was gracious enough to phone to offer his congratulations and laughed uproariously when I told him that the infant, with his tight, pinched baby’s scowl, was a dead ringer for the elderly Ramnath Goenka. They say, in England, I told him, that all new-born babies look like Winston Churchill. We should say, in India, I suggested, that they all looked like Goenka. He was good enough to find this remark — which, in retrospect, I probably should not have made — hugely amusing.

And yet, he never offered me a job again. Even if he had, I doubt if I would have taken it. When you know somebody on a personal level, you get a better sense of what they really think. With Goenka, there was no doubt that he saw most journalists (with some exceptions such as S Mulgaokar) as playthings. He had no respect for professional integrity, regarded most of us as “unscroopoolus” people (which was a bit rich, coming from him) and enjoyed his power to appoint, transfer and sack his editors. Of one of his more famous Punjabi editors, he would say “Saale ko angrezi nahi aati hai” (I’ve cleaned up the quote — Goenka was very big on bad language).

He hired the gentle and thoughtful Darryl D’Monte to run his Bombay edition before also hiring his cousin Dom Moraes to run the Express’s Sunday magazine. Moraes and his wife Leela were frequent dinner guests at the penthouse and, according to Dom, Goenka would begin each conversation with “Sack Monto” — he never quite got his tongue around “D’Monte”. Later, he would describe D’Monte, who is an environmentally-conscious liberal, as “a bloody commie”.

Amazingly enough, in that era, the public at large did not hold his mistreatment of editors against him. Nor did anyone seem to care that he had no time for many of the basic rules of journalism. He would cheerfully use the paper’s news columns to promote his own personal agendas. He would bypass the Express’s journalistic establishment to plant articles written by a coterie of non-journalists to whom he was personally close. BG Verghese recalls being asked to carry an anti-Ambani piece under the by-line of JD Sethi, a Planning Commission member who had clearly not written it. When he refused, Goenka asked that the piece be carried under a generic byline (“By a Correspondent”).

Nor did Goenka make any pretence at objectivity. In the days when I knew him reasonably well, he suddenly turned against Dhirubhai Ambani whom he had, till then, described as his close personal friend. It was not as though Goenka had been unaware that Ambani bent the law to make money (Goenka’s own record in such matters suggests that he himself was no JRD Tata) and, in fact, he would often speak admiringly of Ambani’s many fiddles.

But then something — nobody knows exactly what and even his biographer is not sure — went wrong and Goenka turned against Dhirubhai. “Everybody rapes the system but this man wanted to make it his mistress,” was the only explanation I ever heard him give.

This was fair enough. There’s no doubt that the Ambanis were breaking the law and a good newspaper must expose scams. Except that Goenka went out of his way to not only consort with Ambani’s business rivals but to also claim that he was acting to protect Nusli Wadia, then Ambani’s principal competitor. “Nusli is an Englishman. He cannot handle Ambani. I am a bania. I know how to finish him,” he told me.

The Express’s campaign against Reliance was not run by the paper’s staff but by a small coterie consisting of S Gurumurthy, Goenka’s accountant and advisor, Wadia, Maneck Davar, a journalist who was not on the Express’s rolls, Jamnadas Moorjani, a businessman opposed to the Ambanis and by assorted non-journalist friends and allies of Goenka’s.

In this day and age, it is hard to imagine any proprietor getting away with using his newspaper in this manner, running a personal campaign against somebody on behalf of a business rival without the involvement of his own staff. And yet, in the 1980s, that’s precisely what many people admired Goenka for doing.

Finally, the Reliance campaign was to prove his undoing. Far from being the shrewd bania who would finish off Dhirubhai, Goenka was outwitted by Dhirubhai’s young sons (the father was in San Diego,

recovering from a stroke) who manipulated the situation so skillfully (with the help of forged letters) that a battle between Goenka/Wadia and the Ambanis turned into a national crisis that pitted Rajiv Gandhi against VP Singh (and Goenka). Once this war got underway, the Ambanis simply stepped aside.

Goenka did not realise how cleverly he had been outwitted. His response was to turn against Rajiv instead (which is exactly what the Ambanis wanted him to do) on the grounds that the government was not doing enough to penalise Reliance. After that, the Express lost all sense of proportion. Sleazeballs and racketeers like Chandra Swami

became fixtures at the penthouse, Gurumurthy and Mulgaokar consorted with President Giani Zail Singh and ghost-wrote a hostile letter to the Prime Minister on his behalf, thereby crossing all lines of journalistic propriety. (The Express ran the Mulgaokar-Gurumurthy draft of the President’s letter as a scoop, not realising that Zail Singh had made changes to the letter before sending it to Rajiv. The government then raided the Express guest house in Delhi’s Sunder Nagar and found the original draft with corrections in Mulgaokar’s handwriting.)

By 1988-89, Rajiv’s government retaliated with a series of unnecessary prosecutions. While this response did Rajiv no credit, it also turned the Express into the centre of all opposition to the regime. It ceased to function as a newspaper in any significant sense of the term and became an anti-government pamphlet.

Even then, Goenka retained his iconic stature because, to many people, he seemed to be replaying his heroic defiance of the Emergency regime. (And there’s no doubt that the Congress government behaved disgracefully again.) What people missed was that under this cover of defiance, Goenka was busy putting together a new Opposition alliance. His chosen candidate was VP Singh (who had been part of the anti-Reliance campaign) but Goenka’s real loyalty was to the Jan Sangh/RSS/BJP. His role was to bring the RSS/BJP closer to VP Singh.

Ironically, were Goenka to be around today then many of those who, like myself, admired him in the 1970s because we subscribed to the anti-Congress consensus, would disapprove of him on equally simple-minded grounds. Today, the ruling liberal consensus is secular and there’s no doubt that Goenka and the Express were actually the fore-runners of the BJP’s ascendancy in the 1990s. Or that Goenka was not above using RSS cadres for such commercial purposes as breaking strikes at the Express.

Goenka’s best friends were Nanaji Deshmukh and the Rajmata of Gwalior, both RSS-types. His chief advisor was S Gurumurthy, who is proud of his RSS links. His doctor and advisor was JK Jain (of Jain TV fame) who is hardcore RSS. His most famous editor was Arun Shourie, who later became a BJP minister. His lawyer was Arun Jaitley, who served VP Singh’s government in a legal capacity but found fame as a BJP minister. And the politicians whom Goenka was closest to were nearly all from the BJP.

Did Goenka run a battle against Rajiv on behalf of the BJP? It would make for a neat conspiracy theory but I don’t think there was any grand design to his activities. In 1984, he was ready to end his opposition to Indira Gandhi, calling her “a devi” (Verghese quotes me on this conversation in the book) and by 1985 was singing Rajiv Gandhi’s praises (“I will die a happy man knowing that India is safe in Rajiv’s hands...” etc).

My view remains that the old man was simply outwitted by the two Ambani boys (then in their twenties!) who managed to make Rajiv believe that Goenka’s real agenda was not Reliance, but a coup at the Centre which would result in VP Singh taking over.

Rajiv was politically inexperienced so he was easy to manipulate. But Goenka, who regarded himself as a master manipulator, should have known better. However, rather than see through their game, his first reaction was to lash out in anger. In the process, the Ambani conspiracy theory fulfilled itself. The Express conspired with the President against the Prime Minister, it launched scurrilous (and frequently baseless) attacks on the likes of Amitabh Bachchan and Sonia Gandhi, and eventually, it acted out the Ambani script to the letter by making VP Singh its candidate for PM (only to turn against him when he finally got the job).

At nearly every level, Goenka’s campaign was a failure. The Ambanis are much bigger — and much more legit — than they were in those days. Wadia is much more successful now that he’s not fighting political battles. And the Express’s journalistic credibility was needlessly compromised. Even when a scoop that damaged the Rajiv government did emerge — the Bofors papers — it was The Hindu that got it. The Express’s sole contribution was to try and embellish the Hindu’s scoop with stories that were either speculative or plain wrong and owed their origins to the likes of Chandra Swami.

It is to BG Verghese’s credit — and to today’s Indian Express, given that this is an authorised biography — that he is scrupulously fair. He leaves very little out even when it does not show Goenka in a favourable light. Though he writes with no obvious affection for his subject, he also writes with admiration.

And certainly, there was much to admire in Goenka’s life. At a personal level, I found him warm and human. He demonstrated great courage in the face of odds that would have destroyed a lesser man. He often showed great loyalty to his friends (including the Rajmata of Gwalior and Nusli Wadia).

But his greatest achievement was that he existed at all. Like William Randolph Hearst or Lord Beaverbrook, he was an old-style press baron obsessed with politics and power, impossible to suppress but with an ego that was also impossible to repress.

All this made him one of the great figures of 20th century India. What it did not make him was a force for good journalism. The Indian Express under Shekhar Gupta is a far fairer, much better paper than it ever was under Goenka.

Anyone interested in India in the second half of the 20th century must read this book. Verghese is fair, truthful and always readable.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home